Crawford was born in Memphis and took up the piano aged nine, ![]() soon playing for his church choir. He began playing an alto saxophone his father had brought back from military service so that he could join the Manassas high school marching band, and later to play as an accompanist to King and others. These were the days in which Crawford and his fellow saxophonists would often find themselves walking bar-tops playing, or lying on their backs while the punters threw coins into the saxophone's bell.

soon playing for his church choir. He began playing an alto saxophone his father had brought back from military service so that he could join the Manassas high school marching band, and later to play as an accompanist to King and others. These were the days in which Crawford and his fellow saxophonists would often find themselves walking bar-tops playing, or lying on their backs while the punters threw coins into the saxophone's bell.

soon playing for his church choir. He began playing an alto saxophone his father had brought back from military service so that he could join the Manassas high school marching band, and later to play as an accompanist to King and others. These were the days in which Crawford and his fellow saxophonists would often find themselves walking bar-tops playing, or lying on their backs while the punters threw coins into the saxophone's bell.

soon playing for his church choir. He began playing an alto saxophone his father had brought back from military service so that he could join the Manassas high school marching band, and later to play as an accompanist to King and others. These were the days in which Crawford and his fellow saxophonists would often find themselves walking bar-tops playing, or lying on their backs while the punters threw coins into the saxophone's bell.In 1953 he moved to Nashville to study music theory at Tennessee State College, joining college jazz groups and also leading a ![]() rock'n'roll band, Little Hank and the Rhythm Kings. It was the alto-playing Crawford's resemblance to the celebrated Memphis saxophonist Hank O'Day that earned him his nickname.

rock'n'roll band, Little Hank and the Rhythm Kings. It was the alto-playing Crawford's resemblance to the celebrated Memphis saxophonist Hank O'Day that earned him his nickname.

rock'n'roll band, Little Hank and the Rhythm Kings. It was the alto-playing Crawford's resemblance to the celebrated Memphis saxophonist Hank O'Day that earned him his nickname.

rock'n'roll band, Little Hank and the Rhythm Kings. It was the alto-playing Crawford's resemblance to the celebrated Memphis saxophonist Hank O'Day that earned him his nickname. A Nashville visit from Charles in 1958 led to the 24-year-old Crawford replacing Cooper as the band's baritone saxophonist, and when Cooper returned a year later, the new recruit reverted to the alto. By 1961, his rich early experiences and his formal studies had combined to help him become Charles's musical director as the increasingly popular singer expanded his touring ensemble to a jazzy big band. Crawford later said that the Charles band was like a classroom for him, and that he learned at least as much as he imparted from the experience.

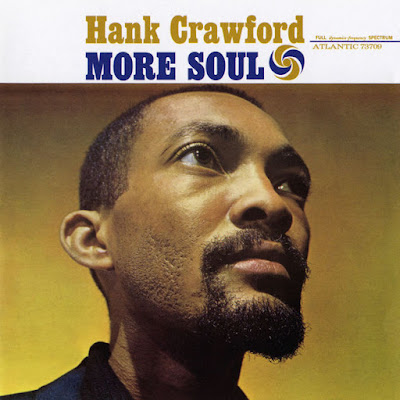

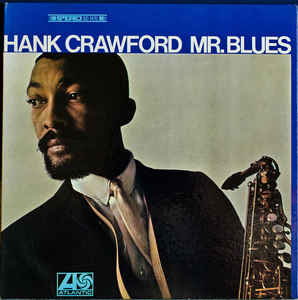

As he had done with Newman, Charles encouraged his eloquent employee to forge a solo career. Crawford recorded extensively for Atlantic in the 1960s, often with Newman on board - his debut, The Art of Hank Crawford (1960), featured fellow musicians drawn ![]() from the Charles contingent - and his sophisticated ear for gospelly "sax-choir" harmonies gave new twists to what could have been formulaic music. Crawford's groups also maintained commercially attractive connections with the Charles sound, and the saxophonist's writing skills brought him chart hits too, such as Misty (1961) and Skunky Green (1964).

from the Charles contingent - and his sophisticated ear for gospelly "sax-choir" harmonies gave new twists to what could have been formulaic music. Crawford's groups also maintained commercially attractive connections with the Charles sound, and the saxophonist's writing skills brought him chart hits too, such as Misty (1961) and Skunky Green (1964).

from the Charles contingent - and his sophisticated ear for gospelly "sax-choir" harmonies gave new twists to what could have been formulaic music. Crawford's groups also maintained commercially attractive connections with the Charles sound, and the saxophonist's writing skills brought him chart hits too, such as Misty (1961) and Skunky Green (1964).

from the Charles contingent - and his sophisticated ear for gospelly "sax-choir" harmonies gave new twists to what could have been formulaic music. Crawford's groups also maintained commercially attractive connections with the Charles sound, and the saxophonist's writing skills brought him chart hits too, such as Misty (1961) and Skunky Green (1964). For all his awareness of 1950s modern jazz, Crawford's sound was rooted in the R&B tradition. His models were the jive-saxophonist Louis Jordan and the technically advanced and commercially successful 1940s altoist Earl Bostic - though he always credited Charlie Parker as a significant influence, and Duke Ellington's alto saxophonist Johnny Hodges.

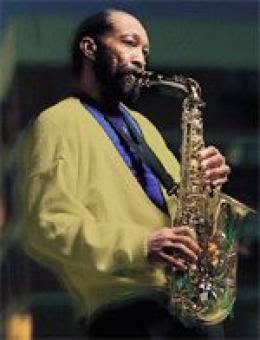

For all his awareness of 1950s modern jazz, Crawford's sound was rooted in the R&B tradition. His models were the jive-saxophonist Louis Jordan and the technically advanced and commercially successful 1940s altoist Earl Bostic - though he always credited Charlie Parker as a significant influence, and Duke Ellington's alto saxophonist Johnny Hodges.Favouring quivering long sounds, emotion-charged vibrato effects, holy-rolling repeating motifs and yearning high notes, Crawford kept the church and blues traditions of his Memphis childhood coursing through his veins, and sounded as much like a vocalist as a saxophonist throughout his working life. He had played with local blues heroes including BB King, Bobby Bland and Junior Parker when he was still in high school, but had also grown up with Phineas Newborn Jr, Booker ![]() Little and George Coleman, all of whom were to become leading lights in the bebop-driven but distinctly churchy hard-bop style of the late 1950s and early 60s.

Little and George Coleman, all of whom were to become leading lights in the bebop-driven but distinctly churchy hard-bop style of the late 1950s and early 60s.

Little and George Coleman, all of whom were to become leading lights in the bebop-driven but distinctly churchy hard-bop style of the late 1950s and early 60s.

Little and George Coleman, all of whom were to become leading lights in the bebop-driven but distinctly churchy hard-bop style of the late 1950s and early 60s.Crawford left Charles in 1963 but had recorded a dozen albums of his own for Atlantic by 1970, followed by eight commercially angled cover albums for Creed Taylor's Kudu. Arrival at the jazz-oriented Milestone company in 1983 allowed him to return to his own muse. His output for the label mixed strong originals with undemanding, easygoing funk, but guests, including Dr John, frequently lifted the temperature.

Through the 1980s and into the 90s, Crawford was also a first-choice guest in high-profile jazz, blues, soul and R&B bands of all ![]() kinds, led by Dr John, Eric Clapton, Etta James, King and the Hammond organist Jimmy McGriff. Like Newman, Crawford's contribution to the development of jazz and R&B melody has been immense, but camouflaged. The Atlantic boss Joel Dorn once wrote: "If musicians had to pay royalties for using someone else's sound the way they have to for recording someone else's songs, David and Hank would be billionaires."

kinds, led by Dr John, Eric Clapton, Etta James, King and the Hammond organist Jimmy McGriff. Like Newman, Crawford's contribution to the development of jazz and R&B melody has been immense, but camouflaged. The Atlantic boss Joel Dorn once wrote: "If musicians had to pay royalties for using someone else's sound the way they have to for recording someone else's songs, David and Hank would be billionaires."

kinds, led by Dr John, Eric Clapton, Etta James, King and the Hammond organist Jimmy McGriff. Like Newman, Crawford's contribution to the development of jazz and R&B melody has been immense, but camouflaged. The Atlantic boss Joel Dorn once wrote: "If musicians had to pay royalties for using someone else's sound the way they have to for recording someone else's songs, David and Hank would be billionaires."

kinds, led by Dr John, Eric Clapton, Etta James, King and the Hammond organist Jimmy McGriff. Like Newman, Crawford's contribution to the development of jazz and R&B melody has been immense, but camouflaged. The Atlantic boss Joel Dorn once wrote: "If musicians had to pay royalties for using someone else's sound the way they have to for recording someone else's songs, David and Hank would be billionaires."Hank Crawford died January 29, 2009 (aged 74) at his home in Memphis, Tenn. He had been in declining health for much of the past year with complications from a stroke in 2000.

(Info compiled and edited mainly from John Fordham’s article in The Guardian)